Gather and Sow: February 2026

Inaugural Note

Welcome to Gather and Sow: The Botanist in the Kitchen Newsletter, our new monthly missive! If you followed our Botanist in the Kitchen blog on the old Wordpress site, we thank you. We will henceforth be posting online content from our new site, powered by Ghost, in newsletter format. We intend to post new issues of Gather and Sow every month. Content on the old blog will generally remain available. We remain dedicated to illuminating the fascinating biology of our food plants.

Each issue of Gather and Sow will feature three components:

- Food for Thought: an essay, possibly seasonal or inspired by current events

- Botany Lab of the Month: a botany lesson for the hands-on learner, packaged as an activity or recipe designed for the home kitchen

- Baker’s Dozen and Gleanings: We highlight thirteen-ish recent research articles and other relevant media, respectively, that further our understanding of the biology of our food plants.

FAQ: Aren’t you two writing a book? Is it done yet? Yes, we are writing The Botanist in the Kitchen book. No, it is not done yet. We have an agent (Hi Lucy!). And a book proposal document. We are close to being done with our sample chapters. Hopefully a publisher will take interest very soon. We’ll post updates with the newsletters.

We would love to hear from you.

You can subscribe to Gather and Sow from the Ghost site. We will also publicize newsletters on the old blog and on social media (Bluesky, Facebook). Please email us at botanistinthekitchen@gmail.com.

Thank you so much for reading.

--Jeanne L. Osnas and Katherine A. Preston

Now on to the introduction to the February 2026 issue:

The archaeological record from the tropical regions of the Americas shows us that chocolate has always been special to humans. Delicious and pharmacologically potent, the seeds of the Theobroma cacao tree were initially reserved for use in rituals. In the modern era, chocolate still accompanies our celebrations. On Valentine’s Day (February 14th), we may acknowledge our beloved with a gift of chocolate. In this month’s Food For Thought essay, “Love and Chocolate,” we briefly trace the history of how chocolate became associated with love. The biology of the plant, in addition to being supremely interesting, has something to do with it.

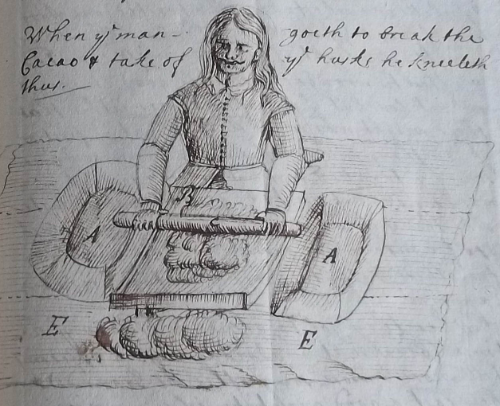

The first processing step in the transformation of Theobroma seeds into modern chocolate confections is the same as it has been since people first started consuming them. The seeds are fermented, roasted, and ground. For several millennia, the processing stopped there, save for blending the mash with hot water and other ingredients to make a beverage–the original hot chocolate. Modern processing then separates the fat in the ground seeds from everything else, collectively called “cocoa solids.” The fat and solids are then mixed back together again in various ratios, along with sugar and other ingredients, for the final product.

The primary fat in Theobroma seeds–cocoa butter–is unique, as well culinarily and ecologically significant. Katherine’s quest for perfect homemade white chocolate truffles required a deep dive into cocoa butter’s properties. Katherine’s cocoa butter knowledge and truffle recipe triumphs are recorded in this month’s Botany Lab of the Month (“White Chocolate-Hibiscus Truffles, a botanically-inspired recipe exploration by Katherine Preston”). Theobroma seeds are colloquially called “cocoa beans” in the English speaking world. In this issue, however, we mention that chocolate hails from the mallow plant family (Malvaceae), not the true bean family (Fabaceae). The same goes for coffee (Rubiaceae) and vanilla (Orchidaceae) “beans,” flavors that often accompany chocolate. Katherine discovered that a fellow edible mallow family species, hibiscus, pairs exceptionally well with white chocolate, resulting in a beautifully pink truffle that celebrates the diversity within the plant family.

This month’s newsletter concludes with our round-up of thirteen recent research articles (Baker’s Dozen) and other media (Gleanings) that add to our knowledge of food plants.

Food for Thought

Love and Chocolate

“All you need is love. But a little chocolate now and then doesn’t hurt.” --Charles M. Schulz

Hot (as in tropical) chocolate

Bernal Díaz del Castillo started the rumor that chocolate inspires love—or at least its carnal expression. Díaz del Castillo was a soldier in the entourage of Hernán Cortés, the Spanish conquistador who destroyed the Aztec Empire in 1521. Before the conquest, when the Spanish were still considered welcome guests of Emperor Montezuma II, Cortés and his party attended a lavish feast in the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, modern day Mexico City. They witnessed the ritualized presentation and consumption of a beverage made from cacao seeds—the original hot cocoa—served in elaborately decorated earthenware vessels. Recording his observations from the event, Díaz del Castillo later wrote that he had been told that Montezuma drank cacao before visiting his wives (1). Despite this purported incentive, the Spanish failed to drink cacao on that occasion, or much at all, during their earliest contacts with Mesoamerican cultures. Cacao—ground seeds of the Theobroma cacao tree—was generally not sweetened in its original incarnations, and the Spanish conquistadors found it distasteful. Perhaps occasionally the mixture of ground cacao seeds and water was dosed with a small amount of honey, but it was far from sweet. Typically the traditional preparation included ground chilies, cornmeal, and sometimes vanilla or other herbs and spices.

Even if they did not want to actually drink cacao, the Spanish conquistadors readily observed that the seeds were a valuable commodity. Cacao in Mesoamerica was almost exclusively a food of the nobility and upper class elites. The seeds were in fact a form of currency throughout the region at the time of the Spanish conquest, and the Aztec Emperors in Tenochtitlan—where cacao did not grow—demanded annual tribute of several tons of dried cacao seeds from the cacao growing regions of the Empire (2–4). Cacao seeds were treasured and used to solemnize important rituals, events, or transactions: ceremonies of birth, death, marriage, kingship (5, 6).

The reverence with which Mesoamerican people regarded the cacao plant was acknowledged by eighteenth-century Swedish biologist Carl Linnaeus when he named the genus Theobroma. It means “food of the gods,” a nod to both Mayan and Aztec myths that ascribe divine origin to the plant (1, 5, 7). Quetzocoatl, the Aztec’s feathered serpent god, found the plant in a heavenly valley, according to one story. And cacao seeds are even part of the Mayan creation story; the seeds were watered with the blood of a god and grew people. The species name cacao is a derivative of several similar-sounding words used in Mesoamerica to describe the drink made from the seeds, which they fermented, dried and roasted before grinding. The words “cocoa” and “chocolate” were later European inventions.

Stimulating company

The earliest evidence of consumption of cacao was from the northern Amazon River basin, 5000 years before, and considerably south of, the Aztec Empire (8–13). The evidence consists of trace organic residues on pottery shards that either contain DNA identifiable as from Theobroma, or are rich in caffeine and theobromine, the key active ingredients in chocolate (theobromine is the chemical precursor to caffeine and accumulates at high levels in Theobroma seeds) (5, 14–17).

Not many plants around the world—less than 100 species—are caffeinated (18). Most, if not all, of them were independently identified by indigenous peoples in their localities and used as medicinal beverages and in religious rituals (4, 5, 19–25). Several caffeinated plants are native to the Americas: cacao and its close relatives in Mesoamerica and the Amazon Basin; the holly shrubs yerba mate and guayusa (Ilex paraguaensis and Ilex guayusa) in South America, and yaupon and dahoon holly in North America (Ilex vomitoria and Ilex cassine); and guarana (Paullinia cupana), also in the Amazon Basin. None of these American sources of caffeine are in the same plant family, nor are they closely related to coffee (genus Coffea), from Africa, or tea (Camellia sinensis), from Asia. Cacao is, however, in the same plant family (Malvaceae, the mallow family) as caffeinated kola nuts (genus Cola, one of the ingredients in cola soda), from Africa. Cacao and kola, however, are not particularly closely related within the Malvaceae, so caffeine synthesis likely evolved independently in each genus, rather than in a common ancestor of both.

It is not clear why such a large fraction of the world’s caffeinated plants are from the Americas. Perhaps it is only a matter of chance; the forests of the Amazon River basin and Central America account for a large fraction of the planet’s plant species diversity (26). Caffeine and its attendant alkaloids (like theobromine) are potently insecticidal and possibly also allelopathic (herbicidal to seedling competitors) (20, 27–31), and perhaps this defense function simply serves it well in the American forest setting.

Creatures great and small

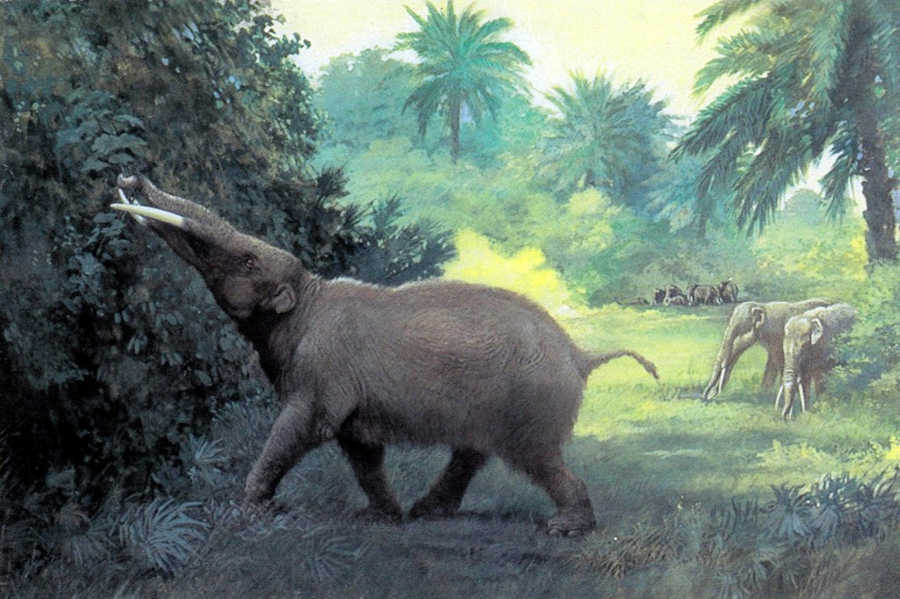

And while these stimulants clearly also serve humans well, cultivation and harvest by humans has benefitted the cacao plants in turn. Humans have proved to be effective seed dispersing mammals for our favorite plants. This is especially fortuitous for Theobroma and other similar understory species in the Neotropics. For much of their evolutionary history, seed dispersal in these taxa was accomplished by large herbivorous mammals, including ground sloths and mastodon relatives called gomphotheres. Most of these enormous symbionts went extinct during the Pleistocene, ecologically stranding the plants that depended on them (32–39). Without humans and other animals to harvest their fruits and spread their seeds, these taxa could have been lost (40, 41).

The co-evolution of Theobroma and its seed dispersers of old may explain some of its unusual characteristics, including its large fruits and seeds. Cacao trees are relatively short (around 20 feet for cultivated specimens) and live in the shaded understory of wet tropical forests (within 20 degrees latitude of the equator). Unlike most other trees that bear their flowers and fruit on the tips of small branches, cacao flowers emerge directly from the wood of their trunk or large branches, a strategy called cauliflory. The ovoid cacao fruits grow to around twelve inches long, resulting in the odd appearance of brightly colored football-shaped fruits hanging from short stalks directly from the trunk.

Like caffeine, cauliflory pops up in a relatively small number of species that are not closely related to one another. There is no definitive explanation for cauliflory, but the strategy does allow its practitioners to physically separate reproduction (flowering and fruiting) from photosynthesis (done by leaves). In cacao, the cauliflorous habit is likely an evolutionary adaptation that assists with either flower pollination—accomplished primarily by midges that are no bigger than the period at the end of this sentence, including the dreaded biting “no-see-ums”, that rise out of the piles of rotting vegetation on the forest floor (43, 44)—or seed dispersal by large mammals (45). Tiny midges and roaming mammals might have preferred flowers and fruits located within easy reach of the forest floor, even if the cacao tree canopy was much taller.

Theobroma cacao growing in a large glasshouse in the Atlanta Botanical Garden, exhibiting cauliflorous flowers and fruits (fruits in this variety are orange when ripe). Photos by K. Preston.

From cacao to cocoa

No contemporaneous accounts corroborate Díaz del Castillo’s assertion that cacao was a Mesoamerican love potion, but there are numerous written records from the Catholic monks and friars who accompanied and followed the Spanish colonists that report on other medicinal uses of cacao by Mayan and Aztec healers. Nonetheless, the legend of cacao as a potent aphrodisiac became tangled with its reputation as a healthful food and followed the seeds back to Spain, carried initially by Catholic missionaries returning home, and later by merchants (1).

Spanish missionaries in the New World developed a taste for cacao and were probably the first to mix it with another tropical commodity—sugar. Clergy returning from the New World introduced the Spanish nobility to sweetened drinking chocolate, and it remained the province of the European aristocracy—and later wealthy North American colonists—even after chocolate moved beyond the Iberian Peninsula. Only after sugar became generally affordable in the 1700s (because of slave labor in Central American and Caribbean plantations) did drinking chocolate become popular with ordinary Europeans and North American colonists.

Chocolate’s reputation as an aphrodisiac accompanied its march across Europe (1, 5, 6, 14, 25, 46–48). Notorious seventeenth-century libertines Giacomo Casanova and the Marquis de Sade loudly celebrated chocolate’s potency and drank massive amounts of the stuff. England’s Charles II spent more each year on chocolate than he did on his (numerous) mistresses—or on tea. In a cleverly titled episode “Hot for Chocolate,” historians Averill Earls and Elizabeth Garner Masarik of the DIG podcast provide an excellent overview of the history of cacao importation in Europe and its aphrodisiac reputation (47). They discuss how the 2000 movie Chocolat, starring Juliette Binoche and Johnny Depp, showcases the fear and fascination that chocolate elicited in provincial Europeans as it made its way across the continent–with decidedly erotic overtones.

Nineteenth-century Swiss confectioners were the first to make chocolate candies (1). Instead of just drinking chocolate, the world then had chocolate bars and truffles. The invention of chocolate candy marks the beginning of the commercial marriage of chocolate and romance. Europeans had marked Saint Valentine’s Day as a celebration of romantic love since the fourteenth-century English poet Geoffrey Chaucer published his poem “Parliament of Fowls,” in which birds choose their mates on Saint Valentine’s Day. But it was the Victorians who tied Valentine’s Day to chocolate. Richard Cadbury, the founder of the British confectionery that bears his name, was the first to make a heart-shaped box and stuff it full of chocolate bon-bons. These hit the London market in 1861 and were a smash hit. Recipients kept the boxes long after the chocolates were eaten as a receptacle for keepsakes and treasures. American versions of the Valentine’s boxes of chocolates were soon to follow suit, and the trend was punctuated when Hershey invented the “kiss” in the 1920s.

Today there is no scientific evidence that chocolate consumption has a measurable effect on the relevant human physiology, but five centuries of good marketing has sealed its reputation as Cupid’s confection of choice. Modern medicine does acknowledge that cacao can beneficially contribute to a healthy diet, much like other large, fatty seeds that we casually call “nuts” (5, 14). And, of course, they are loaded with stimulants, caffeine and theobromine. Chocolate likely preceded coffee and tea in many sixteenth-century European cities and was therefore the first caffeinated foodstuff experienced by the people fortunate enough to consume it (49).

Consuming chocolate, then, might not make you feel physiologically amorous, but you will feel alert, and probably happy, because chocolate is delicious. Gifting happiness to someone you love is certainly a good investment. So, in a way, as with the Aztecs and Maya, cacao is still a valuable currency. Investing in sustainably grown cacao is also a way to show love to our tropical forests. Cacao trees prefer shaded understories, which mean that they are best grown in concert with other tree species, a forest structure also preferred by cacao’s pollinating insects. Farmers growing shaded cacao are thereby able to gain income from multiple tree crops, and a more diverse parcel of tropical forest benefits wildlife (50).

Botany Lab of the Month

White Chocolate-Hibiscus Truffles, a botanically-inspired recipe exploration by Katherine Preston

Keeping it in the (mallow) family

White chocolate is not technically chocolate, as the confection is usually rendered. It lacks the cocoa solids that give genuine chocolate its rich complex flavor borne of hundreds of aromatic compounds balanced by just a touch of sour and bitter. However, proper white chocolate is made from cocoa butter, the purified fat component of the Theobroma cacao seeds from which true dark chocolate is also made. Raw cocoa butter has its own subtle scent and creamy texture, and I thought I could use it to make a version of white chocolate more to my liking than commercial versions, with less sugar and no stale milk flavor.

It turns out that working with cocoa butter is tricky, but it gave me the chance to learn a lot more about the nature of this finicky fat. It also turns out that sugar and some kind of milk powder are essential ingredients in all the homemade white chocolate recipes I found, because they seem to make the fat easier to work with. My plan was to make white truffles, which would showcase homemade white chocolate as an ingredient but allow me to balance its unavoidable sweetness with another flavor.

Because it can be fun and instructive to find a culinary match within the same botanical family, I searched for a balancing flavor from the list of common edible members of the Malvaceae (the mallow family). Baobab? Too hard to find locally. Durian? Too risky. Linden tea? Too subtle. Okra? No. Just no. Hibiscus? Bright red and tangy and perfect. Although hibiscus and Theobroma are rarely united in cooking – and they took divergent evolutionary paths about 90 million years ago (51) – I found that these plants work extremely well together. Unlike traditional dark rich chocolate truffles, white cocoa truffles rolled in crimson hibiscus powder melt in your mouth like cool and fluffy snowballs, followed by a refreshing sour kick.

The African species Hibiscus sabdariffa, sometimes called roselle, is the most widely available hibiscus for culinary use. It is often used to make a colorful and tangy herbal infusion (“tea”). Because of its global popularity its flowers can sometimes be bought dried and in bulk at co-ops or international markets. The petals are relatively short, and so a whorl of fleshy sepals makes up most of the flower, as is obvious after they have been plumped back up by a soak in hot water.

Cocoa butter

Melting and molding dark chocolate into candies is notoriously difficult because the chocolate can lose its temper (in the technical, not metaphorical, sense) and become grainy or develop white oily streaks as it cools. The trouble lies in the cocoa butter, and like many chocolate dilettantes, I became interested in cocoa butter behavior when I tried to learn how to keep my dark chocolate in temper.

Cocoa butter is the fat that Theobroma cacao stores in its seeds to fuel the growth of its seedlings. Like many of the large edible seeds we casually call nuts, cacao seeds are about half fat by weight, but their fat composition is very different from the fat found in almonds, walnuts, or even the ecologically similar Brazil nuts (52). In plants and animals, all naturally occurring fat is composed almost entirely of triglycerides, which are based on a glycerol backbone with three fatty acid tails. Those fatty acids can be long or short, and straight (saturated) or kinked (unsaturated). The nature of the tails determines how the individual triglyceride molecules interact to form crystals and whether the fat will be liquid or soft or firm at room temperature (53). Very generally, the more straight tails there are, the more closely and stably the triglyceride molecules can be packed together, and the firmer the fat will be (54).

Whereas milk fat includes about 400 different kinds of fatty acids (55), cocoa butter is dominated by only three (56). That simple chemical profile isn’t unusual for seeds, but the types and proportions are. Cocoa butter triglycerides mostly contain two long, straight fatty acids (palmitic and stearic) and one long kinked one (oleic), in fairly equal proportions (56). The high percentage of stearic acid is especially unusual and contributes to the solid state of cocoa butter at room temperature, while the equal combination of these three particular fatty acids causes cocoa butter to melt quickly on our skin or in our mouth.

Another unusual property of cocoa butter is that it actually cools your mouth when it melts. A piece of chocolate on your tongue gradually warms, and at first you feel it approaching your body temperature. However, precisely at its melting point – just below body temperature – it abruptly stops getting warmer, even as it continues to remove heat from your mouth, thereby cooling it. This pause in warming is due to the high latent heat of fusion of the triglyceride molecules. Because it happens just below body temperature, you feel a cooling sensation.

Interestingly, the exact proportions of the three fatty acids varies slightly with genotype and environmental conditions during the growing season (57). Cocoa butter is, ultimately, food for cacao tree seedlings, and so the precise fatty acid composition of the seeds certainly reflects the species’ seed ecology. To my knowledge, the details have not yet been investigated, but I assume that the fat properties influence both seed longevity under hot tropical temperatures and the ability of seedlings to metabolize the fats as they draw on them for energy during germination. In any case, because the exact proportions of the three fatty acids determines the melting point of cocoa butter, its source and genotype will also affect its behavior in our kitchens or in a factory.

Making truffles (basic recipe and white chocolate-hibiscus version)

The basic recipe: Traditional dark chocolate truffles are pretty simple to make: Simmer some cream and let it cool to the point where you might consider taking a very hot bath in it. Herbs or spices may be steeped in the cream during the simmer (and strained out after the flavor has enriched the cream). Measure the volume of the hot cream in ounces and add twice as many ounces by weight of finely chopped chocolate. Stir gently to melt all the pieces and then allow the mixture (called ganache) to cool at room temperature. Overheating the chocolate initially or cooling the ganache too fast takes the chocolate out of temper. When the ganache is firm, roll it into lumpy balls, coat with cocoa powder, lick your fingers, et voilà.

Coming up with a good homemade white chocolate truffle is harder. It turns out that dark chocolate is much more forgiving than pure cocoa butter when it comes to truffles. The first time I tried to make white cocoa truffles, I followed my usual recipe, using chopped cocoa butter in place of dark chocolate and adding some sugar with the cream. Although I was extremely careful not to overheat the cocoa butter, my ganache separated anyway. Whereas dark chocolate contains cocoa solids that support the desired type of crystal formation in solidifying chocolate (58), cocoa butter does not. In my various experiments with the gentle melting of cocoa butter, I went so far as to sit for an hour on a plastic bag full of grated cocoa butter. Although it should have melted at body temperature, it never got quite soft enough. I finally got the texture right when I accepted a century of professional wisdom and introduced the dreaded milk powder as well as a lot of sugar into the recipe.

Slightly suspect variants: Note that you can buy white “chocolate” chips and use them in place of dark chocolate in the usual truffle recipe described above. I tried this and it worked when I increased the chips-to-cream ratio to slightly above 2-to-1. However, do read the ingredient list because many white chocolate chips (especially those labeled “white morsels”) contain no cocoa butter at all. The gomphotheres would not approve.

If you would like to make a different type of pink chocolate truffle to complement your white chocolate-hibiscus creations, consider following the general truffle recipe with ruby chocolate. The exact origin of the pink tint of ruby chocolate is a trade secret, known definitively only by confectioner Callebaut, which patented the ruby chocolate production process (59). Chocolate experts, however, suspect that ruby chocolate is made from unfermented seeds from a particular variety of cacao, which has been anecdotally observed to make especially pink seeds (60, 61). Before they are fermented and roasted, which darkens the color, cacao seeds are whitish-gray with pink and lavender highlights.

White chocolate-hibiscus truffles

Ingredients

- 3 oz food grade pure cocoa butter, chopped

- 1/2 cup powdered sugar

- 1 1/2 teaspoons powdered milk

- 1/4 cup cream

- 1/4 cup sugar

- hibiscus powder (see step 1 in the Instructions, below) from 5 or 6 dried hibiscus flowers

Instructions

- To make the hibiscus powder truffle coating, it is necessary to grind dried flowers to the finest possible powder and sieve out any remaining gritty pieces. I pulverized about half a dozen flowers in a retired coffee grinder, but you can use a mini food processor or a spice grinder. I quickly learned to let the powder settle before opening the grinder, to avoid getting a Gomphothere-sized dose of astringent dust in my human-sized nose. After grinding, the powder must be sifted through the finest sieve you can manage. I use a gold filter like those designed to filter coffee. It takes time and patience but this step is important for the look and the mouthfeel of the truffles. The sieve full of leftover grit makes a nice cup of tangy tea.

- In a small food processor, pulverize the cocoa butter, powdered sugar, and powdered milk. The result should be coarse dry crumbs. Place the crumbs in a small heatproof bowl or the top of a double boiler.

- Bring the cream to a simmer and dissolve the sugar in it. (For one version I steeped a couple of hibiscus flowers in the cream, which tasted good but made the truffles pink all the way through. Extra cream was needed to account for some of it clinging to the flowers, which were subsequently strained out.)

- When the cream is the temperature of a hot bath, pour it into the cocoa butter mixture. Remember, cocoa butter melts below body temperature so the cream doesn’t have to be very hot. The crumbs will cool the cream as you stir, and you want the mixture to be just above body temperature as the centers of the crumbs are melting. Those last bits to melt will seed the mixture with the desired type of crystals and favor their formation as the mixture cools.

- It will take several hours for the mixture to be firm enough to roll into balls. I usually leave it at room temperature overnight. Do not rush the process by chilling it! Fast cooling favors unstable crystals and your truffles will be grainy.

- Roll the mixture into balls and roll them in the hibiscus powder.

Baker's Dozen and Gleanings

Baker’s Dozen

These are thirteen-ish of the papers that piqued our interest thus far in 2026.

- A few perspectives on different aspects of domestication:

- Cao et al. (2026). Plant domestication revisited: Genomic insights into origins, mechanisms, and convergent evolution. iScience 29, 114062. An exceedingly useful review.

- Hernandez-Teran et al. (2026). Plant domestication does not reduce diversity in rhizosphere bacterial communities. New Phytologist 249: 1968-1979. Commentary on the paper is here.

- Snodgrass et al. (2026). Maize genetic diversity is largely unstructured by human ethnolinguistic diversity in its center of origin. Preprint. This is reminiscent of excellent work done a few years ago by Maggioni et al. (2018) that linked the domestication pattern of Brassica oleracea to its descriptions in Greek and Latin texts.

- AJB’s Special Issue: Paradigm Shifts in Flower Color has two articles that we particularly liked that both investigate correlated patterns of color evolution in flowers and fruits. Fruits develop from the ovaries of flowers, but the two reproductive stages evolutionarily respond largely independently to the abiotic environment and animal mutualists.

- Dellinger et al. (2026). Does the abiotic environment influence the distribution of flower and fruit colors? American Journal of Botany 113, e70044. A global perspective.

- Sinnott-Armstrong et al. (2026). Flower clades and fruit clades: Trade-offs in color diversification in angiosperms. American Journal of Botany 113, e70146. The researchers investigated relative evolutionary lability of flower and fruit color in clades with animal-pollinated flowers or animal-dispersed fruits–meaning fleshy fruits, including several that humans like to eat.

- For those keeping tabs on agricultural impacts of climate change, here are two worthwhile papers addressing different physiological responses:

- Li et al. (2026). The optimization of crop response to climatic stress through modulation of plant stress response mechanisms. Opportunities for biostimulants and plant hormones to meet climate challenges. New Phytologist 249, 130-151. A review with a readable description of plant stress response mechanisms.

- Caine et al. (2026). Future heatwave conditions inhibit CO2-induced stomatal closure in wheat. New Phytologist 249: 1234-1252. Experimental manipulation of CO2 and heat.

- The first New Phytologist issue of the year also had two articles that demonstrate that a small change in a gene can have a big impact on an agronomically significant characteristic in two different vegetables from the genus Brassica:

- Cui et al. (2026). A 48-bp deletion within the promoter of the BnaC9.APT5 gene results in elevated seed number per silique in Brassica napus. New Phytologist 249, 270-281. The varieties of B. napus grown for oil seed are called canola or rapeseed. The number of seeds per fruit dramatically affects yield.

- Cheng et al. (2026). Intronic transposon insertion within the MYB transcription factor gene BjPur disturbs anthocyanin accumulation by inducing epigenetic modification in Brassica juncea. New Phytologist 249, 325-341. Mustard greens from B. juncea can be quite colorful, exhibiting a range of purples and greens. A simple genetic change identified by the researchers switches leaf color from purple to green.

- Hoefle et al. (2026). Fruit function beyond dispersal: effect of fruit decomposition on the plant microbiome assembly. New Phytologist 249: 1442-1455. We’re convinced. So noted.

- Clark et al. (2026). Climate drives variation in optimal phenology: 46 years of multi-environment trials in sunflower. New Phytologist 249: 1527-1541. An extraordinary quantification of climate impacts on flowering time and seed set in oilseed sunflower.

- Ikeda et al. (2026). The mid-SUN-POD1 complex ensures the structural integrity of ER bodies required for herbivore defense in Arabidopsis. New Phytologist 249: 1770-1784. A mustard bomb in the endoplasmic reticulum, as described in the commentary here. This may or may not be relevant to cruciferous vegetables (same family as Arabidopsis), but it’s always nice to check in with recent research on the mustard bomb. And it’s weird that it’s in the ER.

- Zhang et al. (2026). Calcium signaling in crops. New Phytologist 249: 1644-1658. An excellent review of all things calcium in crop plants.

- Ozowara et al. (2026). Variability in apple fruit quality across management systems and latitudinal climate gradients. Plants People Planet 8: 212-230. A comparison of quality in organically versus conventionally grown domestic apples, from southern California through northern Washington. Growing method matters far less than climate. In that same issue of PPP:

- Sari et al. (2026). Gene duplication, horizontal gene transfer, and trait trade-offs drive evolution of postfire resource acquisition in pyrophilous fungi. PNAS 123: e2519152123. Yes, we know that fungi are not plants, but fire-loving shrooms are so cool! And they include some of the delicious morel species, some of the time. This recent paper explains how they make a living on burned soils.

- Westbrook et al. (2026). Genomic approaches to accelerate American chestnut restoration. Science 391: 730-735. Checking in with chestnuts. Commentary here.

- Pangenomics of some crop plants with complicated situations in Science, with commentary by Soltis2:

Gleanings

Assorted recent relevant media that we noticed

- Rendering cotton seeds toxin-free, from NPR

- Gastropod podcasts–we’re going through the back catalog

- A botanical highlight of Bad Bunny’s Super Bowl halftime performance was the sight of running sugarcane, as dancers dressed as the grass streamed on and off the field. We can only hope that it is an auspicious American version of Birnam Wood marching toward Dunsinane Hill. Kudos to Bad Bunny for teaching Americans that sugar comes from a grass.

- Knowable Magazine from Annual Reviews is great. A few recent articles cover:

References

1. L. E. Grivetti, H.-Y. Shapiro, Chocolate: History, Culture, and Heritage (John Wiley & Sons, 2011).

2. K. E. Sampeck, A constitutional approach to cacao money. J. Anthropol. Archaeol. 61, 101257 (2021).

3. J. P. Baron, Making money in Mesoamerica: Currency production and procurement in the Classic Maya financial system. Econ. Anthropol. 5, 210–223 (2018).

4. A. Ford, A. Williams, M. S. de Vries, New light on the use of Theobroma cacao by Late Classic Maya. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 119, e2121821119 (2022).

5. M. T. Montagna, G. Diella, F. Triggiano, G. R. Caponio, O. D. Giglio, G. Caggiano, A. D. Ciaula, P. Portincasa, Chocolate, “Food of the Gods”: History, Science, and Human Health. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16 (2019).

6. T. L. Dillinger, P. Barriga, S. Escárcega, M. Jimenez, D. S. Lowe, L. E. Grivetti, Food of the Gods: Cure for Humanity? A Cultural History of the Medicinal and Ritual Use of Chocolate. J. Nutr. 130, 2057S-2072S (2000).

7. M. Rusconi, A. Conti, Theobroma cacao L., the Food of the Gods: A scientific approach beyond myths and claims. Pharmacol. Res. 61, 5–13 (2010).

8. C. Lanaud, H. Vignes, J. Utge, G. Valette, B. Rhoné, M. Garcia Caputi, N. S. Angarita Nieto, O. Fouet, N. Gaikwad, S. Zarrillo, T. G. Powis, A. Cyphers, F. Valdez, S. Q. Olivera Nunez, C. Speller, M. Blake, F. J. Valdez, S. Raymond, S. M. Rowe, G. S. Duke, F. E. Romano, R. G. Loor Solórzano, X. Argout, A revisited history of cacao domestication in pre-Columbian times revealed by archaeogenomic approaches. Sci. Rep. 14, 2972 (2024).

9. C. R. Clement, M. J. Ferreira, M. F. Cassino, J. F. de Moraes, Domestication of Amazonian landscapes. Estud. Av. 38, 55–72 (2024).

10. M. Colli-Silva, J. E. Richardson, E. G. Neves, J. Watling, A. Figueira, J. R. Pirani, Domestication of the Amazonian fruit tree cupuaçu may have stretched over the past 8000 years. Commun. Earth Environ. 4, 401 (2023).

11. C. R. Clement, M. D. Cristo-Araújo, G. C. D’Eeckenbrugge, A. A. Pereira, D. Picanço-Rodrigues, Origin and Domestication of Native Amazonian Crops. Diversity 2, 72–106 (2010).

12. C. Levis, F. R. C. Costa, F. Bongers, M. Peña-Claros, C. R. Clement, A. B. Junqueira, E. G. Neves, E. K. Tamanaha, F. O. G. Figueiredo, R. P. Salomão, C. V. Castilho, W. E. Magnusson, O. L. Phillips, J. E. Guevara, D. Sabatier, J.-F. Molino, D. C. López, A. M. Mendoza, N. C. A. Pitman, A. Duque, P. N. Vargas, C. E. Zartman, R. Vasquez, A. Andrade, J. L. Camargo, T. R. Feldpausch, S. G. W. Laurance, W. F. Laurance, T. J. Killeen, H. E. M. Nascimento, J. C. Montero, B. Mostacedo, I. L. Amaral, I. C. Guimarães Vieira, R. Brienen, H. Castellanos, J. Terborgh, M. de J. V. Carim, J. R. da S. Guimarães, L. de S. Coelho, F. D. de A. Matos, F. Wittmann, H. F. Mogollón, G. Damasco, N. Dávila, R. García-Villacorta, E. N. H. Coronado, T. Emilio, D. de A. L. Filho, J. Schietti, P. Souza, N. Targhetta, J. A. Comiskey, B. S. Marimon, B.-H. Marimon, D. Neill, A. Alonso, L. Arroyo, F. A. Carvalho, F. C. de Souza, F. Dallmeier, M. P. Pansonato, J. F. Duivenvoorden, P. V. A. Fine, P. R. Stevenson, A. Araujo-Murakami, G. A. Aymard C., C. Baraloto, D. D. do Amaral, J. Engel, T. W. Henkel, P. Maas, P. Petronelli, J. D. C. Revilla, J. Stropp, D. Daly, R. Gribel, M. R. Paredes, M. Silveira, R. Thomas-Caesar, T. R. Baker, N. F. da Silva, L. V. Ferreira, C. A. Peres, M. R. Silman, C. Cerón, F. C. Valverde, A. Di Fiore, E. M. Jimenez, M. C. P. Mora, M. Toledo, E. M. Barbosa, L. C. de M. Bonates, N. C. Arboleda, E. de S. Farias, A. Fuentes, J.-L. Guillaumet, P. M. Jørgensen, Y. Malhi, I. P. de Andrade Miranda, J. F. Phillips, A. Prieto, A. Rudas, A. R. Ruschel, N. Silva, P. von Hildebrand, V. A. Vos, E. L. Zent, S. Zent, B. B. L. Cintra, M. T. Nascimento, A. A. Oliveira, H. Ramirez-Angulo, J. F. Ramos, G. Rivas, J. Schöngart, R. Sierra, M. Tirado, G. van der Heijden, E. V. Torre, O. Wang, K. R. Young, C. Baider, A. Cano, W. Farfan-Rios, C. Ferreira, B. Hoffman, C. Mendoza, I. Mesones, A. Torres-Lezama, M. N. U. Medina, T. R. van Andel, D. Villarroel, R. Zagt, M. N. Alexiades, H. Balslev, K. Garcia-Cabrera, T. Gonzales, L. Hernandez, I. Huamantupa-Chuquimaco, A. G. Manzatto, W. Milliken, W. P. Cuenca, S. Pansini, D. Pauletto, F. R. Arevalo, N. F. C. Reis, A. F. Sampaio, L. E. U. Giraldo, E. H. V. Sandoval, L. V. Gamarra, C. I. A. Vela, H. ter Steege, Persistent effects of pre-Columbian plant domestication on Amazonian forest composition. Science 355, 925–931 (2017).

13. M. Colli-Silva, J. E. Richardson, J. R. Pirani, A. Figueira, Wild or Introduced? Investigating the Genetic Landscape of Cacao Populations in South America. Ecol. Evol. 15, e71746 (2025).

14. P. Afoakwa MPhil Eo., Cocoa and chocolate consumption – Are there aphrodisiac and other benefits for human health? South Afr. J. Clin. Nutr. 21, 107–113 (2008).

15. X.-Q. Zheng, Y. Koyama, C. Nagai, H. Ashihara, Biosynthesis, accumulation and degradation of theobromine in developing Theobroma cacao fruits. J. Plant Physiol. 161, 363–369 (2004).

16. M. Aneja, T. Gianfagna, Induction and accumulation of caffeine in young, actively growing leaves of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) by wounding or infection with Crinipellis perniciosa. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 59, 13–16 (2001).

17. H. Ashihara, H. Sano, A. Crozier, Caffeine and related purine alkaloids: Biosynthesis, catabolism, function and genetic engineering. Phytochemistry 69, 841–856 (2008).

18. T. Suzuki, G. R. Waller, “Metabolism and Analysis of Caffeine and Other Methylxanthines in Coffee, Tea, Cola, Guarana and Cacao” in Analysis of Nonalcoholic Beverages, H.-F. Linskens, J. F. Jackson, Eds. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 1988; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-83343-4_11), pp. 184–220.

19. Caffeine and theobromine analysis of Paullinia yoco, a vine harvested by indigenous peoples of the upper Amazon | Tropical Resources Institute. https://tri.yale.edu/tropical-resources/tropical-resources-vol-34/caffeine-and-theobromine-analysis-paullinia-yoco-vine.

20. H. Ashihara, A. Crozier, Caffeine: a well known but little mentioned compound in plant science. Trends Plant Sci. 6, 407–413 (2001).

21. R. Huang, A. J. O’Donnell, J. J. Barboline, T. J. Barkman, Convergent evolution of caffeine in plants by co-option of exapted ancestral enzymes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 10613–10618 (2016).

22. H. Ashihara, T. Suzuki, Distribution and biosynthesis of caffeine in plants. Front. Biosci. 9, 1864–1876 (2004).

23. H. J. Smit, “Theobromine and the Pharmacology of Cocoa” in Methylxanthines, B. B. Fredholm, Ed. (Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg, 2011; https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-13443-2_7), pp. 201–234.

24. D. L. Lentz, T. L. Hamilton, S. A. Meyers, N. P. Dunning, K. Reese-Taylor, A. A. Hernández, D. S. Walker, E. J. Tepe, A. F. Esquivel, A. A. Weiss, Psychoactive and other ceremonial plants from a 2,000-year-old Maya ritual deposit at Yaxnohcah, Mexico. PLOS ONE 19, e0301497 (2024).

25. D. Lippi, Sin and Pleasure: The History of Chocolate in Medicine. J. Agric. Food Chem. 63, 9936–9941 (2015).

26. B. A. Hawkins, R. Field, H. V. Cornell, D. J. Currie, J.-F. Guégan, D. M. Kaufman, J. T. Kerr, G. G. Mittelbach, T. Oberdorff, E. M. O’Brien, E. E. Porter, J. R. G. Turner, Energy, Water, and Broad-Scale Geographic Patterns of Species Richness. Ecology 84, 3105–3117 (2003).

27. H. F. Burger, K. Hylander, B. Ayalew, N. M. van Dam, E. Mendesil, A. Schedl, T. Shimales, B. Zewdie, A. J. M. Tack, Bottom-up and top-down drivers of herbivory on Arabica coffee along an environmental and management gradient. Basic Appl. Ecol. 59, 21–32 (2022).

28. V. T. T. Pham, T. Ismail, M. Mishyna, K. S. Appiah, Y. Oikawa, Y. Fujii, Caffeine: The Allelochemical Responsible for the Plant Growth Inhibitory Activity of Vietnamese Tea (Camellia sinensis L. Kuntze). Agronomy 9 (2019).

29. J. A. Ceja-Navarro, F. E. Vega, U. Karaoz, Z. Hao, S. Jenkins, H. C. Lim, P. Kosina, F. Infante, T. R. Northen, E. L. Brodie, Gut microbiota mediate caffeine detoxification in the primary insect pest of coffee. Nat. Commun. 6, 7618 (2015).

30. J. A. Mustard, The buzz on caffeine in invertebrates: effects on behavior and molecular mechanisms. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71, 1375–1382 (2014).

31. Y.-S. Kim, Y.-E. Choi, H. Sano, Plant vaccination: Stimulation of defense system by caffeine production in planta. Plant Signal. Behav. 5, 489–493 (2010).

32. F. A. Smith, E. A. E. Smith, C. P. Hedberg, S. K. Lyons, M. I. Pardi, C. P. Tomé, After the mammoths: The ecological legacy of late Pleistocene megafauna extinctions. Camb. Prisms Extinction 1, e9 (2023).

33. H. S. Rogers, I. Donoso, A. Traveset, E. C. Fricke, Cascading Impacts of Seed Disperser Loss on Plant Communities and Ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 52, 641–666 (2021).

34. M. S. Lima-Ribeiro, D. Nogués-Bravo, L. C. Terribile, P. Batra, J. A. F. Diniz-Filho, Climate and humans set the place and time of Proboscidean extinction in late Quaternary of South America. Palaeogeogr. Palaeoclimatol. Palaeoecol. 392, 546–556 (2013).

35. M. T. Alberdi, J. L. Prado, Diversity of the fossil gomphotheres from South America. Hist. Biol. 34, 1685–1691 (2022).

36. Y. Malhi, C. E. Doughty, M. Galetti, F. A. Smith, J.-C. Svenning, J. W. Terborgh, Megafauna and ecosystem function from the Pleistocene to the Anthropocene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 113, 838–846 (2016).

37. J.-C. Svenning, R. T. Lemoine, J. Bergman, R. Buitenwerf, E. L. Roux, E. Lundgren, N. Mungi, R. Ø. Pedersen, The late-Quaternary megafauna extinctions: Patterns, causes, ecological consequences and implications for ecosystem management in the Anthropocene. Camb. Prisms Extinction 2, e5 (2024).

38. M. M. Pires, The Restructuring of Ecological Networks by the Pleistocene Extinction. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 52, 133–158 (2024).

39. P. R. G. Jr, M. Galetti, P. Jordano, Seed Dispersal Anachronisms: Rethinking the Fruits Extinct Megafauna Ate. PLOS ONE 3, e1745 (2008).

40. M. van Zonneveld, N. Larranaga, B. Blonder, L. Coradin, J. I. Hormaza, D. Hunter, Human diets drive range expansion of megafauna-dispersed fruit species. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 115, 3326–3331 (2018).

41. M. Colli-Silva, J. E. Richardson, A. Figueira, J. R. Pirani, Human influence on the distribution of cacao: insights from remote sensing and biogeography. Biodivers. Conserv. 33, 1009–1025 (2024).

42. Gomphotherium - The Early Miocene Elephant. https://www.fossilguy.com/gallery/vert/mammal/land/gomphotherium/index.htm.

43. I. H. S. Torquato, R. G. de Souza, M. M. Maués, C. C. Castro, Flies and Cocoa: The Key to Global Chocolate Production. J. Appl. Entomol. 149, 1513–1519 (2025).

44. M. A. Jaramillo, J. Reyes-Palencia, P. Jiménez, Floral biology and flower visitors of cocoa (Theobroma cacao L.) in the upper Magdalena Valley, Colombia. Flora 313, 152480 (2024).

45. T. Wibaux, P.-É. Lauri, A. A. M’Bo Kacou, O. Pondo Kouakou, R. Vezy, A spatial perspective on flowering in cauliflorous cacao: architecture defines flower cushion location, not its early activity. Ann. Bot. 136, 309–323 (2025).

46. K. Loveman, Chocolate in Seventeenth-century England and Spain: An Edited Transcript of the Earl of Sandwich’s Journal. Food Hist. 20, 95–128 (2022).

47. A. Earls, Hot for Chocolate: Aphrodisiacs, Imperialism, and Cacao in the Early Modern Atlantic, DIG (2020). https://digpodcast.org/2020/07/05/hot-for-chocolate-aphrodisiacs-imperialism-and-cacao-in-the-early-modern-atlantic/.

48. K. Loveman, The Introduction of Chocolate into England: Retailers, Researchers, and Consumers, 1640–1730. J. Soc. Hist. 47, 27–46 (2013).

49. P. Withington, Where Was the Coffee in Early Modern England? J. Mod. Hist. 92, 40–75 (2020).

50. T. Tscharntke, Y. Clough, S. A. Bhagwat, D. Buchori, H. Faust, D. Hertel, D. Hölscher, J. Juhrbandt, M. Kessler, I. Perfecto, C. Scherber, G. Schroth, E. Veldkamp, T. C. Wanger, Multifunctional shade-tree management in tropical agroforestry landscapes – a review. J. Appl. Ecol. 48, 619–629 (2011).

51. R. Hernández-Gutiérrez, S. Magallón, The timing of Malvales evolution: Incorporating its extensive fossil record to inform about lineage diversification. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 140, 106606 (2019).

52. T. Chunhieng, A. Hafidi, D. Pioch, J. Brochier, M. Didier, Detailed study of Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) oil micro-compounds: phospholipids, tocopherols and sterols. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 19, 1374–1380 (2008).

53. E. Thomas, M. van Zonneveld, J. Loo, T. Hodgkin, G. Galluzzi, J. van Etten, Present Spatial Diversity Patterns of Theobroma cacao L. in the Neotropics Reflect Genetic Differentiation in Pleistocene Refugia Followed by Human-Influenced Dispersal. PLOS ONE 7, e47676 (2012).

54. D. Manning, P. Dimick, Crystal Morphology of Cocoa Butter. Food Struct. 4 (1985).

55. N. Garti, N. R. Widlak, Cocoa Butter and Related Compounds (Elsevier, 2015).

56. G. Griffiths, J. L. Harwood, The regulation of triacylglycerol biosynthesis in cocoa (Theobroma cacao) L. Planta 184, 279–284 (1991).

57. G. M. Mustiga, J. Morrissey, J. C. Stack, A. DuVal, S. Royaert, J. Jansen, C. Bizzotto, C. Villela-Dias, L. Mei, E. B. Cahoon, E. Seguine, J. P. Marelli, J. C. Motamayor, Identification of Climate and Genetic Factors That Control Fat Content and Fatty Acid Composition of Theobroma cacao L. Beans. Front. Plant Sci. 10 (2019).

58. L. Svanberg, L. Ahrné, N. Lorén, E. Windhab, Effect of sugar, cocoa particles and lecithin on cocoa butter crystallisation in seeded and non-seeded chocolate model systems. J. Food Eng. 104, 70–80 (2011).

59. E. Tuenter, M. E. Sakavitsi, A. Rivera-Mondragón, N. Hermans, K. Foubert, M. Halabalaki, L. Pieters, Ruby chocolate: A study of its phytochemical composition and quantitative comparison with dark, milk and white chocolate. Food Chem. 343, 128446 (2021).

60. J. Pickering, A chocolate expert explains what Ruby chocolate is and what it tastes like, Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/what-ruby-chocolate-tastes-like-according-to-an-expert-2017-10.

61. J. Jay, New ruby chocolate isn’t special and probably tastes bad, says NZ expert, Stuff (2017). https://www.stuff.co.nz/life-style/food-wine/food-news/96786751/new-ruby-chocolate-isnt-special-and-probably-tastes-bad-says-nz-expert.